As we acknowledge June as Indigenous Heritage Month in Canada, heritage specialists in the field of architecture should reflect on the rich history, heritage, resilience and diversity of Canada’s First Nations, Inuit and Metis Peoples. In the ancestorial and unceded territories of Anishinaabe and Algonquin Peoples, the National Capital region is home to Indigenous Peoples from all over turtle island, and our local architecture should be reflective of such.

Indigenous architects are underrepresented in the architectural profession in Canada. The current percentage of Indigenous Architects in Canada remains in the double digits, a low 0.3% of all registered architects across the country (2018). This means that Indigenous-led design is significantly under-represented in our built environment. The Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) has recognized the need to increase Indigenous representation in the field of architecture and has been actively working to promote diversity and inclusivity. The RAIC’s Indigenous Task Force was established to address these issues and support the development of Indigenous architects.

Indigenous architects and designers play a crucial role in promoting Indigenous design principles, cultural values, and sustainable practices. They contribute to projects that incorporate Indigenous perspectives, traditional knowledge, and respectful engagement with Indigenous communities.

Canadian Museum of History

The National Capital is home to a notable building, the Canadian Museum of History, designed in 1983 by Indigenous architect Douglas Cardinal. The construction began in 1984 and was completed in 1989, a process that was fast-tracked and often leaving some design considerations unresolved when construction began. The building’s design is inspired by the topography and context of the natural systems of the site. Cardinal’s style is attributed to designing structures that appear to rise out of the land rather than sitting on top of it, making use of curvilinear forms to manipulate light and shadow.

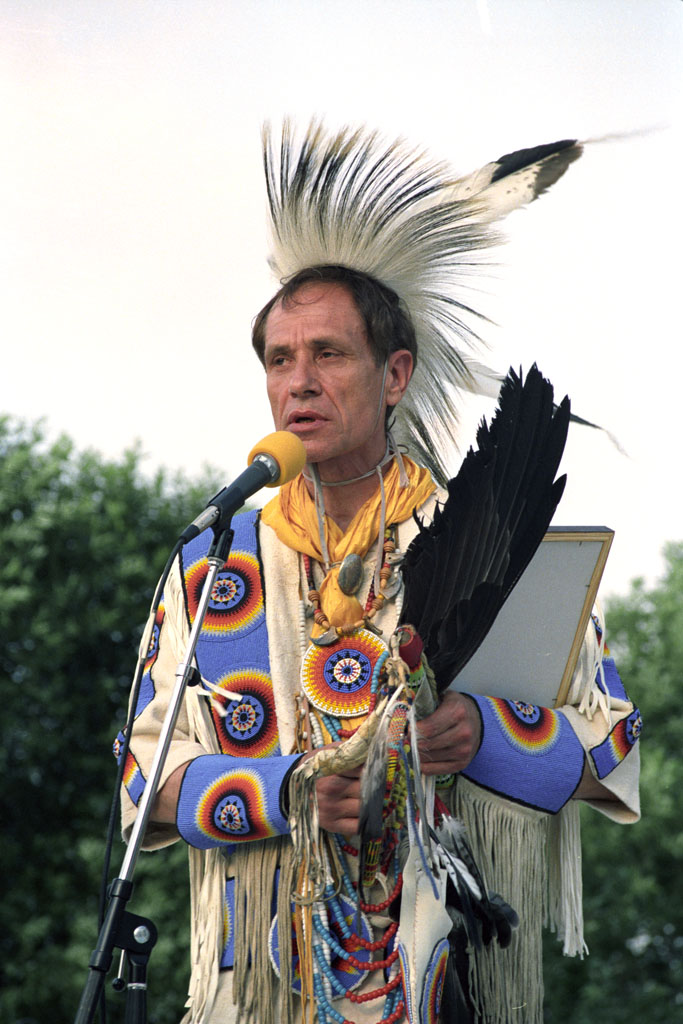

"Instead of viewing the museum as a sculptural problem, instead of identifying all the historical forms and making them the vocabulary for my solutions, I prefer to take a walk in nature, observe how nature has solved its problems, and let it be an inspiration to me in solving mine."

Douglas Cardinal

Cardinal’s design of the Museum of History was one of the first instances where Computer-Aided Design (CAD) was used in Canada, and Cardinal’s firm was considered one of the leading firms in North America to push CAD software to the limits of its performance and identify new applications of its use.

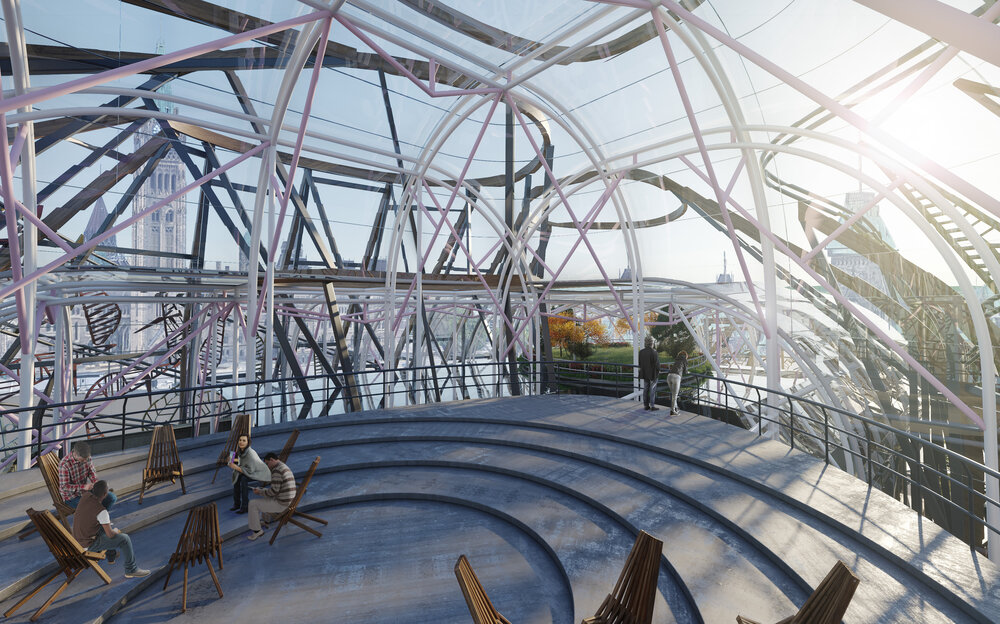

Indigenous People's Space

The Indigenous People’s Space is a part of the 2017 Federal Announcement for the former US Embassy to be repurposed into a national space for Indigenous Peoples in Ottawa on the traditional, unceded territories of the Algonquin Nation. The site will be between 100 Wellington, 119 Sparks Street—connecting the two by an infill.

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN), with Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and the Metis National Council, partnered with David T. Fortin Architect, Wanda Dalla Costa, Eladia Smoke and Elder Winnie Pitawanakwat to develop a design to inspire the long-term vision for the Indigenous Peoples Space. The proposal displays design excellence, with Indigenous symbolism representing the country’s diverse First Nations, Inuit and Metis Peoples.

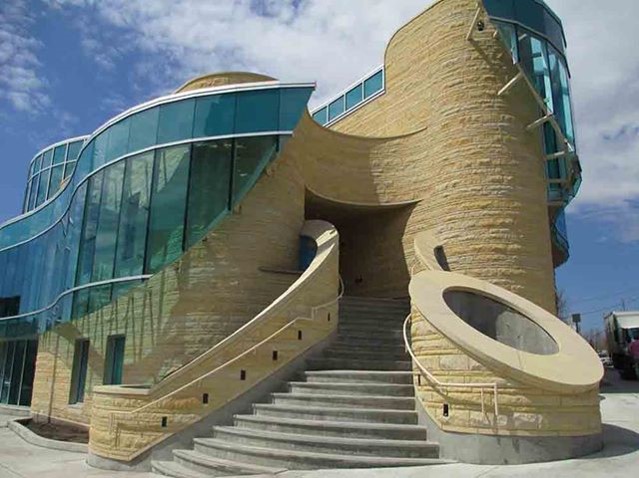

Webano Centre

The Webano Centre opened in 2013, designed by Douglas Cardinal and his son Bret, is along Montreal Road in the Vanier neighbourhood of Vanier. The building’s curvaceous walls are a strong design element, contrasting a rough-cut stone with blue-green glass. The stone is the same Minnesota Lime used in the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau. The Webano Centre offers health, social services, counselling and cultural services for Ottawa’s Indigenous community. The project’s exterior brings awareness of an otherwise “invisibility” of the Indigenous population in Ottawa.

Both in its interior and its exterior, the centre incorporates numerous First Nations symbols—particularly those tied to female symbolism like the moon, circles and water to reflect the centre’s focus on aboriginal women’s health. The dome is supported by 13 columns corresponding with the 13 lunar cycles in a solar year. The ceiling is painted in four blocks of red, yellow, white and black to indicate the four directions. Coloured tiles on the floor resemble a traditional star blanket pattern—the eight-pointed morning star heralding a new beginning or “Wabano” in Ojibwe.

Ottawa Citizen

Indigenous Centre - Algonquin College

The Indigenous Centre at Algonquin College was designed by Indigenous Design Studio Brook McIlroy, with Diamond Schmitt Architects and J. Cuhaci Architects. The building incorporates Indigenous design elements, including a circular shape representing the Medicine Wheel, and incorporates sustainable and eco-friendly features. Ishkodewan, meaning there is fire, is the name of the outdoor courtyard, with a gathering circle and fire vessel.

Horticultural industries students participated in the planting of more than 100 plant species that have cultural and historical significance to Indigenous Peoples for their medicinal, nutritional or cultural properties. The courtyard garden is the outdoor component of the College’s newest facility, the DARE District, which opened 2018.

Algonquin College Library Renewal & Institute for Indigenous Entrepreneurship | Brook McIlroy

These precedents remind us that indigenous design is, and has always been, a part of the Capital Region. As we continue to strive for meaningful reconciliation in action, it’s important to look to our local examples of astonishing Indigenous architecture. Indigenous design elements, storytelling, and cultural symbolism are a part of our city’s fabric, fostering a sense of cultural identity and promoting cross-cultural understanding of place. By incorporating Indigenous designs in our landscape and architecture, the Capital Region can celebrate our country’s First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples, and their contributions to the architectural landscape.

Moving forward, it’s crucial to continue fostering relationships and collaborations with Indigenous communities and architects to create more opportunities for Indigenous-led design projects in Ottawa. This includes supporting educational programs that empower Indigenous individuals to pursue careers in architecture and design, as well as engaging in meaningful consultations and partnerships with Indigenous stakeholders when planning and developing future architectural projects.

By embracing and integrating Indigenous designs, Ottawa can become a vibrant, inclusive, and culturally diverse city that recognizes and respects the Indigenous heritage that shapes its identity.